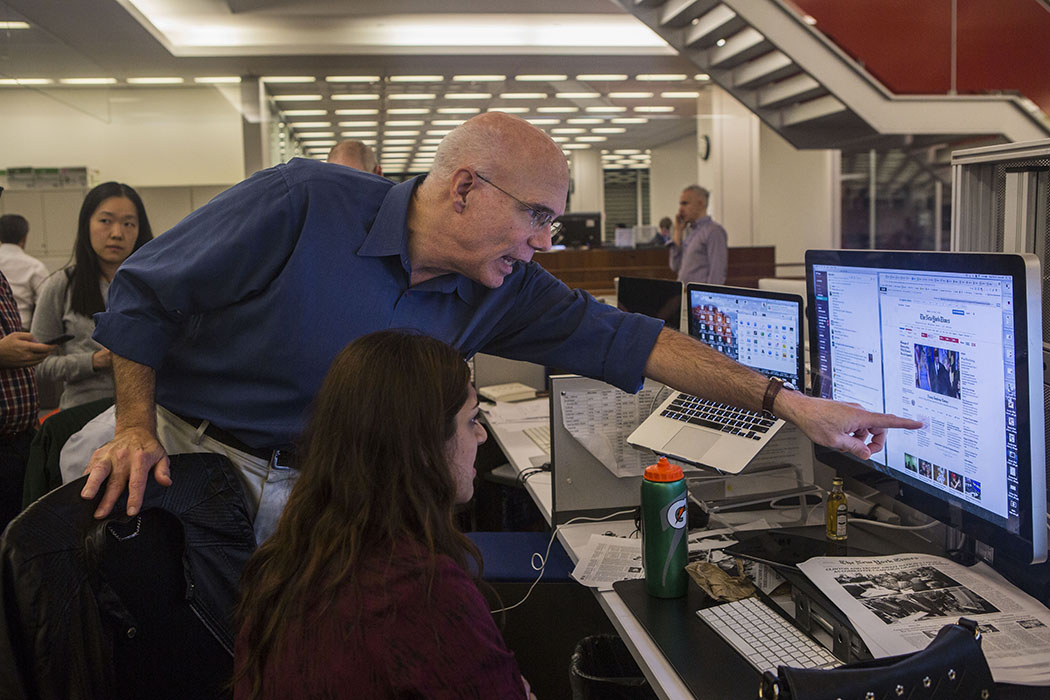

Steve Kenny working at The New York Times’ newsroom in New York on election night, Nov. 8, 2016.

(Photo by Hiroko Masuike/The New York Times)

Steve Kenny barely can recognize his childhood neighborhood.

When the New York Times senior editor was 10 years old, he relocated from New Jersey when his parents purchased a four-bedroom ranch house on Brookshire Drive in 1966. The neighborhood near St. Mark’s School felt like the countryside to Kenny. Visible for miles, the library was the sole building on Royal Lane, back when Hillcrest Avenue was home to a horse stable.

As Dallas grew, Kenny watched the Galleria sprout out of a cotton field, the Dallas North Tollway replace freight railway tracks and the middle-class neighborhood that he called home transform into one of city’s most desirable.

“The land is still there. The street names are the same, but you go down the blocks, and none of the houses are there,” Kenny says. “It’s sort of like the invading army came through in one fell swoop, erased every home and built new houses.”

Even though the city has changed, Kenny vividly recalls the people and places that shaped his youth, from NorthPark Center to his Hillcrest journalism teacher Julia Jeffress, who was instrumental to Kenny’s success. The Northwestern University graduate honed his skills at the Dallas Morning News before landing a gig as a copyeditor at the New York Times. He’s now the night editor, overseeing operations at the world’s most high-profile newspaper.

What happened to your childhood home?

It was torn down around 2004. It was at 6424 Brookshire Drive. It was a four-bedroom house — old ranch-style. My parents bought it for $30,000 in 1966. In that time, in that part of Preston Hollow, the streets were not paved. We had concrete, and there were no curbs. In the summertime, the trucks would come by with the tar and gravel. In the heat of the summer, the tar would sometimes get sticky. We’d always make our mother so mad to come inside the house with fresh tar on the soles on our feet. Starting in the late ‘60s and ‘70s, a block could vote about whether they wanted their streets paved with cement and gutters put in.

What was the neighborhood like?

When we first moved there until I was well into high school, there was no development on the eastern side of Hillcrest. There was no development on the western side of the tollway. Once you got past Forest Lane, the city petered out. There wasn’t anything from Forest Lane until you got up to Richardson, and no one really talked about Plano, because no one knew Plano was there.

The other thing about the neighborhood then is Sears had first built the store on Preston Road in what became Valley View Mall. It just sat by itself. You could see it forever. It looked like the Taj Mahal of retail. One of the first neighbors we talked to was clucking her tongue about the fact Sears had lost its mind by building a store far out in the countryside. No one in their right mind was going to drive all the way out to Sears.

In the past, you’ve compared the neighborhood to “Leave It to Beaver.” Why?

You saw just a lot of kids everywhere, riding their bikes, playing out in the yards the stupid games we played in the ‘60s — kick the can, statue, freeze. We had no options like video games or computers or cellphones. Our mothers always urged us to go outside and play. I wanted to stay inside and read, but my mother would actually lock the door, so I had to go outside and play.

It also was very segregated, not legally segregated. There were no black people who lived in the neighborhood. In the city itself, there weren’t many Hispanics. The census of 1960 shows the percentage of Hispanic people in the City of Dallas was 10 percent. As shameful as it seems now, the only black people we ever saw were the maids who got off the bus at Edgemere and Royal Lane in their uniforms to work in the big houses in Preston-Royal.

Did that ever shift?

It never changed in the neighborhood. I never recall any black people who lived in the neighborhood or Hispanic people in the neighborhood. There were a lot of Jewish people. Within walking distance from my house were the three big synagogues, and the only three synagogues I knew of in Dallas.

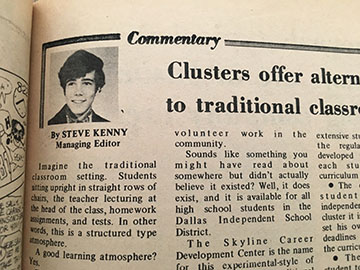

Steve Kenny’s Hillcrest Hurricane staff photo.

Other schools called Franklin “little Israel” and Hillcrest “Hebrew High,” because there was just so many Jewish kids who went to both schools. On my block on Brookshire, I believe that the number of Jewish families outnumbered the number of gentile families on my block.

So that was some sort of diversity, because we were not all Christian. My family was Catholic, which also was some sort of an oddity. I remember when we first moved to the neighborhood, I was in the fourth grade. One of the first things kids asked me is “What are you?” I was not sure what that meant. In many parts of the north, when people say, “What are you?” they’re asking your ethnicity. I said Irish, and they were like, “No, no, no. Are you Baptist? Are you Presbyterian?” I was like, “I’m Catholic.” That was sort of, “Oh, OK, That’s weird.” There was one Catholic Church in the area, and that was Christ the King on Preston Road.

When did the neighborhood start to change?

You first saw it in the early ‘80s. It’s just a thing where the land became more valuable than the structures that were on them.

My mother moved out of our house in 1983 and moved to a house near the intersection of Campbell and Preston Road. My father was gone at that point, and she sold it for over $200,000. That was an incredible amount. I think the people who bought it from her ended up selling it for over $700,000.

One day, I was driving north on Tibbs, and I looked at the roofline. There was a gap, and the house where I lived was gone. I parked the car, and I walked the lot and had memories. The trees in the back had been left, but my mother’s garden, which she had been so proud of, was gone. I went back and watched the construction of the French chateau-like house that replaced it. That was just sad.

Do you feel any history was lost?

Mid-century modern houses are now considered somewhat architecturally significant, and it would’ve been nice if some people had come in there and restored the houses and made them adaptable to 21st-century living. The fact they didn’t is just part of the free market system. I feel sad that my house was bulldozed, but does it affect me personally? Not really.

When you look back, what places do you remember most vividly?

NorthPark opened in 1965. That had had a big impact. It was like a cathedral. We would go there for just a full day to wander around. Where we would go store-wise in the neighborhood was Preston-Royal. There was a Safeway and a Tom Thumb. You were either a Safeway or a Tom Thumb family, and we were a Safeway family. In my head, Tom Thumb families were a little stuck-up, and the Safeway families were a little down-to-earth. That’s the way I looked at it.

Who’s the person you remember most from Hillcrest?

My journalism teacher. Her name is Julia Jeffress. If I had not stumbled upon her, I don’t know what I would be doing now. I doubt very seriously I’d be in New York at the New York Times. I don’t even know if I’d be a journalist. She saw something in me and really encouraged me when I had doubts about myself. She died in 1986 of cancer, and I stayed close until she died.

What memory first comes to mind when you think of her?

One that is stuck in my mind is when I was a senior and managing editor of Hillcrest Hurricane. At that point, it was the ‘70s. They were trying to be hip and change curriculum in the English department to make it “more relevant.” One of the courses they wanted to introduce was Reading, Writing and Rapping. At that point, rapping was sort of a slang term for talking.

We felt this was ridiculous, and we decided to mount an editorial campaign against the changes. This made the English department not happy with us. The chairman of the English department was upset. She came to bawl us out about what we were doing. Ms. Jeffress stood in classroom door, Room 214 at Hillcrest High School, and would not let her pass to berate us. She was very protective of the First Amendment and encouraged us to have a voice.

What attracted you to journalism?

The ability to tell stories and to have other people read them. There’s a book about the New York Times called “The Kingdom and the Power.” It’s by the writer Gay Talese. I read this book when I was 20, and he referred to journalists as “shy egomaniacs.” I think it’s a perfect term, because you want people to read your stuff, but you’re too shy to run up and get attention by yourself. So you hide behind your journalism badge, your journalism notebook. You can ask questions and go places you never would’ve gone if you weren’t a journalist.