Born to be retro

Whether cruising the street was a Saturday night pastime or a way to get a date, cars became engrained in pop culture during the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s. Movies like “American Graffiti” and “Back to the Future” paid homage to vintage automobiles and celebrated what some call the “good ole’ days.” Here in Preston Hollow, many residents restore these classic vehicles to preserve a piece of their free-spirited teenage years.

Ron Rendleman has owned his 1933 Plymouth Coupe since 1957. (Photos by Danny Fulgencio)

Car of a lifetime

Ron Rendleman had a feeling that the 1933 Plymouth Coupe he bought as a Highland Park high-schooler could be something special.

But the Preston Hollow neighbor never expected the car would be his one constant over the past 60 years.

(Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

In 1957, Rendleman cruised around in a reliable, yet lackluster Chevy. The Plymouth Coupe came into his life when a carpenter at his high school made Rendleman an offer: $75 for the pale yellow coupe.

Rendleman was enamored with the vehicle’s short stature and hydraulic breaks. He begged his parents to lend him the money and promised to give them his paper route earnings the following week.

“As soon as I bought this, it changed my entire life,” he

(Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

says. “I just knew I could do something with it.”

The classic car is memorialized in Rendleman’s major teenage milestones. He drove the coupe to his senior prom. His date wore an off-white ball gown that barely fit inside the car. He had to “all but push her into the damn thing.”

He drove it to college at the University of Texas at Arlington, where he was an ROTC student. Rendleman planned to be a commercial airline pilot, but the U.S. Army had other ideas. He received orders to deploy for Vietnam with the 119th Aviation Company only 11 days after he got married. The coupe sat in his parents’ driveway as his family patiently waited for him to come home.

Rendleman transported bodies and dodged bullets in a helicopter for a year before returning to the states. As he walked down the stairs onto the Love Field terminal, he saw his wife, longtime friend and family surrounding the car with the sign “Welcome Home from Viet Nam” on the passenger door. His friend, Allan “Bunky” Garonzik, spent days tinkering with the engine to surprise him.

God Almighty, Rendleman thought.

“I had no idea I was going to walk into the car,” he says. “How Bunky got them to agree to put that on the terminal, I don’t know.”

They thought the gesture would make Rendleman feel a warm welcome home from a controversial war, Garonzik says. The airplane’s passengers zoomed passed the car, but it caught the attention of the Dallas Morning News, who wrote several stories about Rendleman’s near-death experiences overseas.

“I felt, as I recall, that he was a little bit surprised, and he wasn’t expecting anything,” Garonzik says. “Knowing him, he may have been embarrassed.”

When he returned to Dallas, Rendleman got a job as an engineer designing printing equipment, a skill that proved useful when the car underwent major renovations in 1995. Many of the parts, like the hood mechanism and rearview mirrors, he manufactured himself.

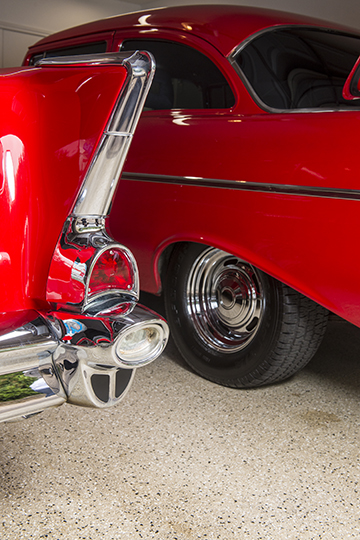

Rendleman initially thought he’d only repaint the car, but it turned into a five-year project. The car’s pale yellow paint was replaced with a bright red coat. He refurbished the interior and replaced the engine.

“I had no earthly idea I was going to go this far with it,” he says.

It’s no longer the only vintage car Rendleman owns. A 1966 Army Jeep is stationed in his yard, and his garage houses a 1933 two-door Plymouth Sedan that his son found on eBay from an East-Coaster.

He alternates displaying each car in shows and won so many awards that he dedicated a room in his house to the trophies.

“I really prefer older cars,” he says. “The technology on Chryslers was so far ahead of any other at the time.”

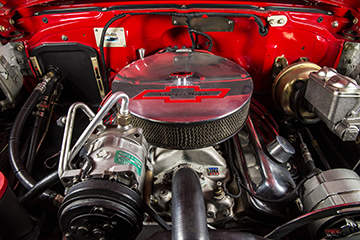

George Caruth’s Chevrolet sedan delivery and two-door sedan pay homage to the year he graduated high school: 1957. (Photos by Danny Fulgencio)

Car kid

Car kid

George Caruth was 17 years old when he owned his first Chevrolet.

If he received all Bs on his report card, his father promised to pay for a Ford, Plymouth or Chevy. The cars weren’t terribly expensive, but they looked distinguished enough that Caruth wouldn’t carelessly leave gum wrappers on its floor.

That was enough of an incentive for Caruth to earn good grades at Highland Park High School.

“When grades got bad, [my father] took the battery cable off of it,” the Preston Hollow neighbor remembers.

“When grades got bad, [my father] took the battery cable off of it,” the Preston Hollow neighbor remembers.

After Caruth graduated, he learned the mechanics of the car so he could drag race at places near Dallas like Caddo Mills and Green Valley, which were popular in the late 1950s and ‘60s. He was hooked on the adrenaline rush of competing, but settling down to raise a family made the hobby shortlived.

“I just didn’t want to do something that might hurt me, and here I am with kiddos and a wife,” he says. “I just had to give up the drag racing, but I didn’t give up my interest in vehicles.”

Even though he’s owned roughly six classic cars since then, he jokes his current 1957 Chevrolets are his children. Like many parents when their kids move away, he missed his two-door sedan when his newlywed daughter brought the car to Denver in 2000. She convinced Caruth that the fire-engine red vehicle would be the perfect getaway car after her wedding. He agreed to leave it at their vacation home in Evergreen, where he only got to drive it three months out of the year.

“I got lonesome for it here in Dallas,” he says.

Caruth’s mechanic caught wind that a man was selling a boxy Chevy sedan delivery that once was used to transport materials for the U.S. Forest Service. Frustrated with the time-consuming renovations, the owner hadn’t reinstalled the vehicle’s engine or transmission, and an empty milk carton was its only seat.

Caruth knew it’d cure his empty-nest syndrome. He dedicated his spare time to having the Chevy restored. Nine months after Caruth bought the vehicle, it was up and running.

“It wasn’t a hobby,” he says. “I certainly haven’t done very many automobiles. It was a challenge to build this car the way I wanted, specifically the engine and transmission that I wanted.”

Caruth sold his home in Colorado four years ago, so both vehicles are back in Dallas. He doesn’t plan to let his kids out of his sight again, he says.

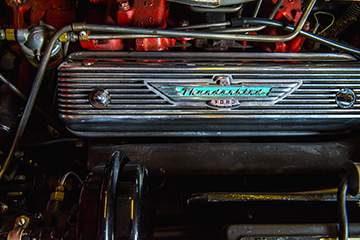

Johnny Brown’s white 1976 Corvette and Von Irwin’s red 1956 T-Bird underwent massive renovations. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

Vintage devotees

Vintage devotees

Johnny Brown keeps his eyes peeled for classic cars when he walks through Northaven Park on his mail delivery route. He’s even known to chase people down the road to compliment their vintage vehicles.

“If I see a classic car of any kind, I’ll walk out in the street to get them to stop,” he says.

(Photos by Danny Fulgencio)

The mailman’s infatuation with automobiles took off as a teen in Wichita Falls, where he spent most weekends racing cars and vying for girls’ attention. He’s the current owner of a 1976 Corvette and a 1971 Torino. His latest project is restoring a 1936 Chevrolet.

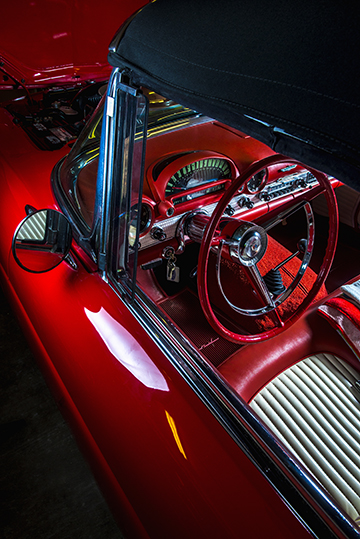

When Brown saw the 1956 Ford Thunderbird that Northaven Park neighbor Von Irwin renovated, the two immediately struck up a friendship. Irwin’s teenage years consisted of joy rides up the Tail of the Dragon, an 11-mile stretch of highway that twists through the Smoky Mountains.

“We grew up in an era where mass transportation was new, and the automobile was the greatest thing of all time,” Irwin says.

They’re proud to have completed much of the restoration work with their own hands. Irwin spent a year holding “Wednesday Night Prayer Service,” where he and his buddies renovated the T-bird. Every nut, bolt and washer was stripped from the car before they replaced the interior and gave it a fresh coat of paint.

“Working on cars, if you hurt yourself, you prayed a lot,” he says.

Irwin and Brown have cut their hands in the midst of repairs more than a few times, but they prescribe to the paper-and-tape treatment plan. It’s given them bragging rights, and they often swap stories.

They don’t mind how tedious renovations can be. It brings them back to their youth, something other generations may not appreciate like they do, Irwin says.

“It doesn’t bother me because I’ll have my classic until the day I go 6-feet under,” Brown says.

(Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

Tyler Wayne with his ‘68 Mercury and his Shelby Cobra reproduction. Both cars are projects Wayne worked on with his dad. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

(Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

American muscle

Tyler Wayne’s dream car was covered in dirt and rust.

Then a high school senior, he kept seeing it, parked in the back of a shop that he used to drive by every day in the Austin neighborhood where he grew up.

Finally one day, he asked the owner about the car, a 1968 Mercury Cougar XR7, and found out it was for sale.

“I asked my dad about it, and he was really excited,” Wayne says.

He paid $1,600 for it in 2004, towed it home on a trailer and started cleaning it up. Thus began a lifelong love of American muscle cars and motorcycles.

Wayne, now 30, is a Southern Methodist University graduate who lives in Preston Hollow and runs Wayne Works, a small business where he makes furniture and lighting.

When he got the Cougar home, its original cranberry-red paint had faded to a flat brown. His dad, always a car guy, was supportive but hands off.

“It was a baptism by fire,” Wayne says.

He read old shop manuals and the history of Ford motors. He learned acetylene welding, how to rebuild the engine and whatever else his project needed. After moving to Dallas for college, he’d continue working on the car during breaks. He finally got it restored, painted it a dark metallic grey and drove it back for his daily driver as an SMU junior.

“It has a lot of sentimental value,” Wayne says. “I’ll never sell that car.”

In 2012, Wayne and his dad decided to begin working on another car they’d always wanted. They bought a 1965 reproduction Shelby Cobra kit from Factory Five Racing.

Wayne is almost giddy when he describes the day it was delivered to his garage. He remembers the exact date: Aug. 22, 2012.

They worked on the Cobra about every weekend, and in February 2013, they painted it Brittany blue, a period correct color. The paintjob alone cost about $7,200, bringing the car total to around $50,000.

They brought it to the annual Cobra Club meet in San Marcos that March and put a couple of hundred miles on it.

Wayne’s mom made a photo memory book of the whole process.

“It’s learning new things, achieving milestones, and doing it all with people you want to spend time with,” he says.

The ’68 Mercury is in pieces right now. Wayne still likes to tinker on it. He and his dad have taken the Cobra on a few other excursions.

Wayne says he still has car goals: A ’67 or ’68 Austin Healey, which he calls “A Sunday gentleman’s car.” He’d also like a ’49 or ’50 Mercury, a “lead sled.” And a ’77 Trans Am because of “Smokey and the Bandit.”

“It’s an element of nostalgia for a time that I didn’t grow up in,” he says. “It’s hard to be in a bad mood when you see a car like that. It makes people smile.” —Rachel Stone

Originally published in May 2017.