Growing waistlines and shrinking budgets have many Americans rethinking their food sources, looking now to local farmers instead of mega-grocers. That national trend is sprouting roots here, which explains why in our neighborhood… IT’S A FARMERS MARKET OUT THERE.

Three years ago in Dallas, if you wanted to buy local produce direct from the grower, the downtown farmers market was just about the only option. Last summer, however, at least half a dozen independent farmers markets mushroomed all over the city.

In our urban context, however, the rise of neighborhood markets has not been without its share of hiccups. Some markets have bumped up against Dallas regulations, which haven’t changed quickly enough to keep up with the new demands.

FROM FROZEN TO FRESHLY PICKED: A DIETARY RENAISSANCE

“People are becoming conscious of what they eat, and if you become a student of local food, you learn that it’s not riddled with hormones and preservatives like the processed stuff you get at grocery stores,” says neighbor Brian Cummings, founder of eatgreendfw.com, an online resource for Dallasites who want to buy from North Texas farmers and ranchers. “People are changing the way they think about food, and that’s changing the way they shop.”

In other words, if they’re not growing it themselves, consumers often want to buy it from local people who are. Thus the recent popularity of neighborhood markets, often dubbed “farmers markets”. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, farmers markets across the nation have grown from just 1,755 in 1994 to 5,274 in 2009. Most of that growth has been very recent: From 2008 to 2009 the jump was 13 percent. That’s significant because the last time the USDA charted farmers market growth, it was for the two-year period between 2006 and 2008, when the number grew by only 6.8 percent.

Cummings has tracked this trend locally, helping to organize several farmers markets, including the one at Milestone Culinary Arts Center in Uptown.

“In addition to the food, people also like the social aspect of local markets,” Cummings says. “There’s a carnival-like aspect with all these things to take in. You get to know the people behind the food you’re buying. You get to know that great Mennonite family known for its great bread. That kind of connection means something to people.”

Ed Lowe, owner of Celebration Restaurant on Lovers near Inwood, instituted a weekly farmers market last summer in his parking lot. Lowe says his eatery serves food made mostly with local ingredients, so the weekly market was “a natural progression”.

“The market was a great hit. We had little old ladies to moms pushing strollers shopping — people even rode their bikes up here. There was a lot of joy in it.”

That is, until the city caught wind of what Lowe was doing.

“A customer had complained that we had a dog on a patio, and I was not aware that we needed to have a permit to have a dog on a patio. So [city officials] came out to notify us of the complaint … on a Saturday. They came here on a Saturday, something that’s never happened in my 38 years of being in business.”

And because it was a Saturday, Celebration was holding its farmers market in the parking lot.

“At first, we didn’t think it would be a big deal because we’d contacted the city twice to tell them what we were doing, and they said we didn’t need any special permits because we’re already running a restaurant here.”

But it turned out to be a big deal. Officials told them they would have to start paying permit fees, or shut down the entire operation.

“First off, they said we could only have a farmers market quarterly, and we were having them weekly. Then they said that they wanted us to start paying about $150 and we had just been charging the vendors $10. So that was the end of the market for us.”

Cummings says this is precisely the problem all of the budding farmers markets across Dallas are now facing.

“One of the issues around farmers markets is that municipals really don’t know how to deal with [farmers markets] — Dallas, for example, doesn’t have a permitting process specifically for them, ” he says.

Right now, the city offers temporary food vendor permits, which are good for only two weeks, and can be used only once every three months. The permits cost $190, plus $5 for every additional booth.

“Sure, that kind of permit is great if you’re working at a food festival or the state fair because you’re making a killing,” Cummings says. “But it’s different for someone at a small farmers market. On a good day these vendors make $200, maybe $300. If you’re asking them to pay that much, you do the math: It’s not proportional, and it doesn’t make sense.

“The problem is how the city is viewing these markets. I don’t think the city should see them as income or tax revenue. They should view these local markets as a way to boost local businesses, and as a service it provides to residents who want local food.”

WILL SMALL FARMERS MARKETS BE ABLE TO SPROUT ROOTS IN DALLAS?

City officials are now reconsidering the way they treat farmers markets. Assistant city manager Jack Ireland is heading a committee of farmers market stakeholders who are brainstorming some possible ordinance changes, specifically for small vendors who want to sell regularly in our city.

That committee has its work cut out for it. City of Dallas spokesman Frank Librio says the city must iron out a whole host of wrinkles before moving forward — zoning, enforcement of health codes and payment of sales tax, just to name a few.

“Some [of the markets] are not allowed based on the current zoning,” he says.

For example, sometimes zoning prohibits the outdoor sale of food.

“The group that’s charged to work on this is trying to come up with a permit process that allows them to override the zoning temporarily,” Librio explains.

Part of the regulatory initiative comes from a fear that the local markets could compete with the downtown Dallas Farmers Market. The City of Dallas owns and operates the nearly seven-decades-old market, and city officials set aside $6.6 million in 2006 bond dollars for infrastructure and improvements to the market. It doesn’t appear that the city will see a payback on its investment in the near future: The 2010 budget for the market includes $1.7 million in revenue, but $1.8 million in expenses.

But the grocery business is one of the most competitive industries, and neighborhood markets don’t take away from the main Dallas market, Cummings says.

“Sure, we will have to spread those markets out so there’s not an oversaturation — after all, we have got to protect the granddaddy [downtown farmers market]. But given our cultural shift toward shopping local, I think there’s now room for multiple farmers markets to survive.”

Plus, he says, most of those who live up north, closer to LBJ Freeway, aren’t driving downtown for produce regularly.

“We need a farmers market or two closer to us.”

According to a memo from city staff to the Transportation and Environment Committee, drafted guidelines on the table allow for no more than 10 neighborhood market locations per year, and they would have to be at least three miles apart from each other. The markets would be allowed to open up shop weekly for a six-hour period, with a limit of 24 occurrences per year. It would also be required that all of the produce sold be grown within 150 miles of the downtown farmers market.

Of course, all of these are just ideas at this point. After reviewing input from city staff and stakeholders, the Transportation and Environment Committee will create a proposal to submit to city council for approval. The hope is to have a policy in place by late spring.

Ultimately, neighbors having more options for local produce will be a win-win situation for neighbors and the downtown market, Cummings says, because it creates a little healthy competition.

“Like they say, rising tides lift all ships: The more farmers markets we have out there competing,” he says, “the better they’ll all get, which will ultimately improve the quality of life for all of us in Dallas.”

KEEPING CRITTERS THAT AREN’T PETS

Shopping for local produce isn’t the only back-to-basics trend on the rise. Raising backyard hens for fresh eggs is becoming more and more common nowadays. Anyone who doubts that simply needs to pick up a copy of Backyard Poultry magazine, or drop in at the next Dallas Backyard Poultry Meetup Group, which is more than 120 members strong and meets monthly at North Haven Gardens.

“I totally take blame for the chicken thing here — that was all my doing,” jokes Leslie Halleck, the general manager at North Haven Gardens. She began a push to start backyard hens at the garden center last year, but much like the farmers markets, it hit a roadblock in terms of city regulations.

“It all came down to a zoning issue,” Halleck explains. “When North Haven Gardens first opened, it was out in the country. But as the city expanded, it annexed this area and we were zoned as residential.

“You can go sell live chickens in front of Walmart because it’s zoned for retail, but we weren’t.”

The city ultimately agreed to change North Haven Gardens’ certificate of occupancy, recognizing hens as garden-related accessories. And the law for homeowners remains the same: Everyone is allowed to keep hens, but roosters are outlawed due to cockfighting.

The local interest in backyard hens has remained popular, Halleck says, with 50 to 100 people showing up every time North Haven Gardens offers a workshop on how to care for the birds. Whether you’re growing your own veggies or buying them locally, whether you’re keeping your own hens or getting fresh eggs at a nearby farmers market — it all boils down to a better quality of life, Halleck says.

“It’s really about controlling your own food. There’s really no reason why us urban dwellers can’t do that. Just because we live in the city, that doesn’t mean we don’t have a right to that.”

The only issue she takes with the back-to-basics trend is the fact that anyone is calling it a “trend”.

“I’m always amused when people call this a trend, like it’s some new concept. People have always grown their own food, and there used to be chickens all over Dallas. It was a very common thing. It was only in recent decades as Dallas became more urban that the practice stopped. It’s certainly not a new thing for Dallas.

“I mean, after all, we are in Texas for Pete’s sake. This lifestyle is our roots.”

Shop local

These farmers markets cropped up last spring and summer, and plan to open up shop again this year, if the city changes its regulations.

Bolsa

614 Davis at Llewellyn

First Sunday of the month

Five vendors who sell produce, meat and locally made gourmet items

Celebration Market

4503 W. Lovers at Elsby

Every Saturday

12 vendors who sell produce, meat, locally made gourmet items and crafts

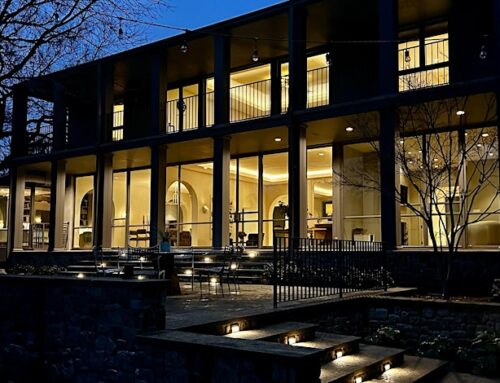

Milestone Culinary Arts Center

4531 McKinney at Knox

Third Sunday of the month, May through November

16 vendors who sell “