The state of Texas has cut education spending drastically. The Dallas school district has more failing schools than ones Exemplary, according to the Texas Education Agency. And sometimes it seems like all the youth of America are going the way of TV’s “Jersey Shore.” That is, they’re narcissistic, promiscuous and disrespectful.

But all of America’s youth are not trashy reality-TV character wannabes. Some of them are great kids, even in the face of adversity.

The following stories showcase a few neighborhood students who have overcome the odds to become successful, college-bound high-school seniors. They prove there is hope after all.

Vanessa Alanis

Vanessa Alanis was almost 11 when she lost her mother.

“I remember it perfectly,” she says, staring straight ahead, her hands clasped in front of her face.

It was May 5, 2004. They had just spent a few weeks visiting family in San Luis Potosí, Mexico. Alanis’s mother received an anonymous phone call that her son Carlos, a runaway, had been spotted back in Dallas. She and Alanis immediately boarded a bus to the airport.

It began to rain. They both fell asleep. What happened next changed Alanis’s life forever.

“I woke up to people screaming,” she says. “As I opened my eyes, I looked for my mom. As she reached to give me her hand, the bus flipped over. I didn’t even blink my eyes before we hit the ground.”

Emergency crews evacuated the bus, and Alanis caught a glimpse of the wreckage — the worst images she has ever seen. She found her mom lying face down on the ground.

“As I lifted her up, her face was full of blood. I said, ‘Mom, wake up!’ ”

She didn’t know it at the time, but her mom was already dead.

From that point on, Alanis shuffled from one dysfunctional family to another. She never knew her father; he left the day she was born. She has a total of seven aunts and uncles scattered around the country. One by one, they passed her off until she finally reached the end of her rope.

“All that unconditional love, I no longer had. I had to mature and grow up. It was difficult.”

At one point, her family advised her to simply quit school and work full time. She knew better than that.

Alanis will graduate from W.T. White High School this summer and attend Texas Woman’s University. She plans to major in biology and enter pre-med in hopes of opening her own plastic surgery practice.

A passion for singing and dancing also keeps her going.

“Every time I dance or sing, I think about my mom,” she says. “I feel comfort because no one can take that away.”

The summer before her senior year, Alanis found herself homeless again. Nonetheless, she headed to drill team camp. On the way, she met Susan Nelson, the hired driver for the carpool. They began talking, and Nelson offered Alanis a place to stay.

“I wanted her to know that there are people out there with good intentions,” Nelson says. “I wanted her to know what it was like to have a home. She practically raised herself.”

It wasn’t easy for Nelson, a mother of four, to bring home an 18-year-old.

“My kids had to be OK with it. They look up to her. They call her sister, and I do think of her as my daughter.”

After being abandoned by every member of her family, Alanis finally found the unconditional love she had been looking for in a complete stranger.

At school, everything about Alanis appears normal from the outside. Most of Alanis’s peers don’t know she doesn’t have parents. Her best friend is Karla Bustillos, a counseling office aid and choir chaperone. Bustillos took Alanis prom dress shopping this year and helped her get ready for the Sadie Hawkins dance.

“I hate to see kids cry, especially when they don’t have a mom and dad,” Bustillos says. “I never want to see a kid suffer. I wouldn’t be in this job if I didn’t care about the kids.”

Alanis has barely seen her older brother Carlos since he left home some weeks before the bus accident eight years ago. By age 13, he had become involved in drugs and crime. She remembers the day he left: She was leaving for a cheerleading game, and he leaned over, kissed her on the forehead and said, “I love you, sis. I’ll see you when you get back.”

When she got home, he was gone, and her mother was sitting on the sofa, crying. She cried for weeks.

“She would ask me to come sit with her and keep her company while she watched TV. I would hold her, and I would feel her tears. I’d ask her what’s wrong, and she’d say, ‘Oh, this soap opera is really sad.’ ”

Every so often, Alanis receives a text from Carlos, “Hey sis, I hope you’re OK.”

As time goes on, she views the trauma of her mother’s death in a different light. Perhaps it was a blessing.

“Four other people died that day. I didn’t have a scratch on me. God gave me a second chance.”

Chelsea Williams

Chelsea Williams is quiet, reserved and surprisingly matter-of-fact about being homeless. It’s all she has ever known.

This fall, the Hillcrest High School senior is headed to Washington University to study oncology. She managed to take nearly all Advanced Placement classes at Hillcrest and still wound up ranking in the top 25 percent of her class while rarely having a permanent place to live.

Williams’ parents divorced when she was 6, but they didn’t tell her until she was 8. It turns out that her father had what Williams says was a secret family — a wife, twin boys and a daughter.

“That’s probably why he was never around,” Williams says.

He called her on her 16th birthday, Williams says, and he sounded as if he had been drinking. That’s the last time she has heard from him.

“With him, it was always promises that were broken. I stopped believing in him.”

After the divorce, Williams’s mother lost their house when her father didn’t pay his half of the mortgage. On top of that, he mother lost her job when her company closed. They moved into an apartment with 10 other family members. At times, they lived in hotel rooms, sometimes skipping out on the bill, she says.

When Williams was 9, her mother moved them to Tacoma, Wash., for a fresh start. Why Tacoma, Wash.? Williams doesn’t know.

“I guess she liked the scenery.”

They lived in a women’s shelter there for one year until her mother could afford an apartment. Many of the residents were drug addicts or mentally ill.

“At my age, I kind of saw it as an adventure. I didn’t really know that it was bad. We were always exploring and experiencing new places.”

She became best friends with an ex-heroine addict’s daughter, who was the same age as Williams. They spent most their days playing with Bratz dolls. Neither of them talked about their situations.

She enjoyed attending school in Tacoma and made good grades. After three years, she and her mom returned to Dallas for a visit but ended up staying when there wasn’t enough money to make it back to Tacoma. The constant apartment hopping continued. They’d move in, get evicted and move on.

They stayed with another aunt in Grand Prairie. By this time, Williams had enrolled in high school. Her mother drove her to Hillcrest on her way to work at whatever retail or fast-food gig she had.

Williams arrived at school early by 7:15 a.m. each day. She’d wait outside the room of her favorite teacher and mentor, Anthony Thomas.

“I get there, and Chelsea is waiting at my door an hour and a half before school starts,” Thomas says. “She knows my door is always open.”

He teaches Algebra 2 and says Williams is among the top students in his class.

“A lot of kids would give up,” he says. “I tell her all the time, life is going to be extremely difficult. You’re going to get just one shot, and you’ve got to make the very best of it.”

After another one of Williams’s aunts learned of their situation, she offered them financial assistance and helped get them settled into a new apartment in January. So far, so good, Williams says.

School has always been Williams’s diversion from her unstable home life. Williams wants to be a pediatrician and loves learning new facts about health.

“In some ways, I pretend I’m like everyone else. It makes me forget about what’s really going on, so I’m able to focus. This is kind of my ticket out of here.”

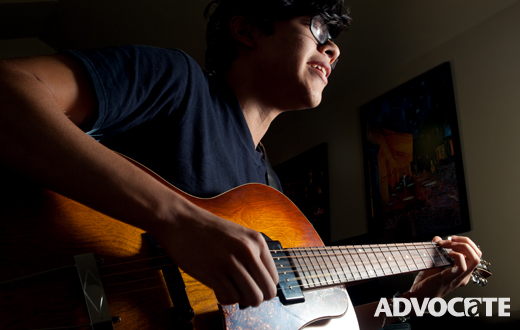

Steven Perez

Steven Perez is an old soul.

He started dealing with adult problems in elementary school. While most third-graders were happy and carefree, he felt depressed and lonely. His dad was in jail. His older brother had been diagnosed with leukemia, and his mom spent most nights with him at the hospital. Perez vividly remembers his brother screaming in pain as doctors inserted a large needle into his back and family stood by, crying.

“I used to have nightmares all the time,” he says. “I was alone a lot. To this day, I like to be by myself. I feel like a recluse.”

His brother beat leukemia, but Perez’s battle was just beginning. He started using heroin at age 12 and says things were better until seventh-grade, when he was caught with it at school.

“I would not be where I am today. I believe in fate and destiny. It was my destiny to get caught.”

He spent one year on probation, meeting with a drug counselor. However, he still took opiates because he missed the good feelings heroin produced.

“It’s an addiction, so I still get urges,” he says. “But that’s where the music comes in.”

W.T. White choir director Michael Parker describes his student as a teenager with the soul of a 50-year-old.

“He likes old-school music,” Parker says. “He’ll come to me with music from the ’60s and even the ’30s. He relates to the older songs. Music is an expression of the soul. Kids get caught up and lost in the shuffle of 2,500 students. They’ve got all of these things pulling at them. That’s where music is different.”

Perez plays in a rock/blues band called Lazy Brother. In 2010, he won the top award at the Bringin’ Down the House competition at the House of Blues, going up against 12 other local high school-aged bands. He did a solo performance of The Cramps’ “Teenage Werewolf.” It was his first real show.

“The audience was cheering, the lights were shining on me,” he says. “It felt really good.”

The next year, he and his three-member band — a drummer and a dancer — returned to the House of Blues to compete against performers from throughout Texas. He won that one, too.

“It lasted until 1 a.m. My band had already gone home. It was just me, my mom, my brother, my friend and my girlfriend. They had announced third and second place. Then they said Lazy Brother. Everyone was quiet except five people in the back screaming their heads off.”

Music has always been a part of Perez’s life. In fact, he was named after Stevie Ray Vaughan. By age 3, he was jamming to The Doors. In fifth-grade, he started playing percussion in band and continued into high school.

It wasn’t until about two years ago that he finally got sober. He remembers the exact day he swore off drugs. He had just performed on the quad (a collection of four drums) at a Dallas ISD Cinco de Mayo parade. He was high, and he couldn’t put the drums back in their case properly. He looked like a fool. In that same moment, his girlfriend Miriam happened to walk by. Their relationship had gone sour, but he still cared for her.

“I was so embarrassed for her to see me the way I was,” Perez says. “I quit that day. She helped me to stop everything. If it wasn’t her for, I’d still be doing a lot of drugs. I think everyone has to find that person who will never give up on you.”

Perez is headed to the University of North Texas to study psychology and join a music program. This old soul is ready to move on from high school.

“High school isn’t everything. People get so caught up in it and don’t realize that you have a whole 50 or 60 years ahead of you.”