(Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

The Prado of Texas

Dallasites don’t need a passport to immerse themselves in Spanish art.

One of the world’s largest collections is located inside the Meadows Museum at SMU. The institution, which features the likes of Francisco de Goya and Pablo Picasso, showcases paintings from A.D. 9 to present day.

“It’s the most comprehensive collection of Spanish art anywhere outside of Spain,” says Janet Kafka, honorary consul of Spain and a member of the museum’s advisory council.

Works of art loaned from high-profile galleries also make guest appearances at rotating exhibitions. In 2010, the Meadows became the first institution to partner with the Prado Museum, Madrid’s esteemed version of the Louvre.

Despite its prestige among art aficionados, the museum is often forgotten by the community, says Bridget Marx, associate director and curator of exhibitions.

“It’s a huge shame, because it’s an amazing collection,” she says.

Its existence is owed to Algur H. Meadows, an oil tycoon with an affinity for Spanish artwork. After exploring the Prado on foreign business trips, he began acquiring original works during the 1950s.

He donated the prized collection to the university in 1962 after the death of his wife, Virginia. He then provided funding to construct the Owen Fine Arts Center, where a museum could be situated.

Three years later, the Meadows Museum opened, but its location didn’t lend itself to large crowds. The works of art spent 40 years tucked inside a hall at the center, where few people outside of the university wandered.

“It wasn’t a space that was fitting for a collection of that caliber,” Kafka says.

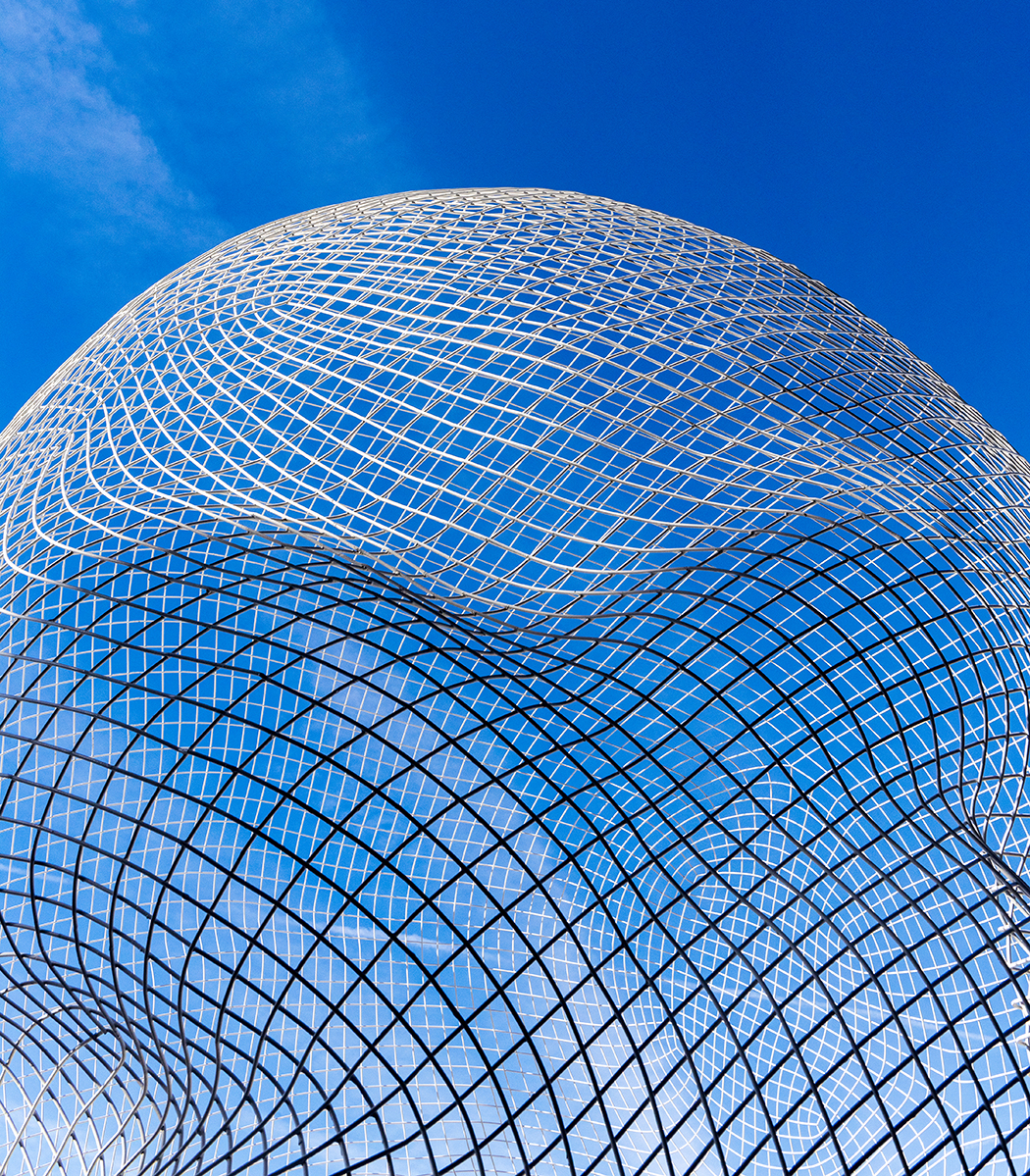

With an $18.5-million donation from The Meadows Foundation, the university decided to build its replacement — one that could accommodate special events and an influx of visitors. It commissioned Hammond Beeby Rupert Ainge to design the two-story, 66,000-square-foot space. The Chicago-based architecture firm’s credentials include renovating the Chicago History Museum and the Toledo Museum of Art.

The museum reopened at 5900 Bishop Blvd. in 2001, and even King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofia attended its inauguration.

“It’s what got Spain to notice the museum,” Kafka says.

Its red brick exterior matches SMU’s Georgian architecture, Marx says, while European galleries inspired its interior design. Open spaces, warm hues and natural light are characteristic of each room.

“One of the things Meadows does that is so extraordinary is they use wall color the way European exhibitions do,” Kafka says. “It makes them very welcoming. You almost feel like you’re in a private home or private villa.”

It now has an auditorium and areas to rent for special events, in addition to a plaza and sculpture garden. This month, avant-garde artist Eduardo Chillida’s sculptures, drawings and collages are on display.

“The galleries are very embracing and accessible and friendly,” Kafka says. “It’s very easy to do a walk-through. Even a first-timer will appreciate the history and the beauty.”

(Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

The art at the Meadows Museum spans from A.D. 9 to today. (Photo by Danny Fulgencio)

Did you know …

The museum received its nickname, “Prado on the Prairie,” in 1968 from Time Magazine after Algur H. Meadows told the Houston Chronicle that he was determined to give Texas its own version of the European museum.

The Meadows Museum ran into trouble not long after its inception when it became apparent some of the works Meadows procured were forgeries. He purchased the art from a Paris dealer, who sold copycat works from “an accomplished copier of the masters, a Hungarian painter named Elmyr de Hory,” according to Meadows’ obituary, published in the New York Times in 1978. Once Meadows discovered the paintings weren’t real, he bought $2 million worth of original art to replace them.

Before the museum reopened in 2001, 27 of its works toured museums across Spain for the first time in history. “Some people cried,” says Janet Kafka, honorary consul of Spain. “Some people said they’d studied these pieces in their art history classes but never knew where they ended up.”