Photography courtesy of Marvin J. Stone

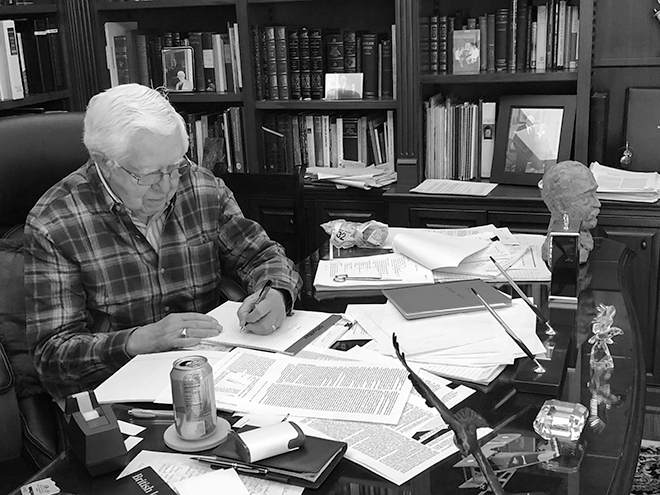

More than 100 years ago, Sir William Osler was redefining medical education. A founding professor of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Osler is considered by many to be the Father of Modern Medicine. Flash forward to 1968, when Dr. Marvin J. Stone arrived in Dallas to wrap up his postgraduate training, passionate about science and people. After what he describes as some “maturing,” he found his way into hematology and oncology, becoming one of three specialists in Dallas. In 1976, he became the first chief of oncology and director of the Baylor Sammons Cancer Center. He spent 32 years at Baylor. Osler has been one of the greatest influences in Stone’s medical career. Stone is literally the president of the American Osler Society. Through medical history research — heavily focused on Osler — Stone encourages a multi-faceted approach to teaching medicine. As a clinical professor of humanities at the University of Texas at Dallas, his class just finished discussing Arrowsmith, Sinclair Lewis’ 1925 novel. Despite retiring from clinical work, Dr. Stone is still active in the Dallas medical community. He’s chief emeritus of hematology and oncology at Baylor University Medical and a professor of internal medicine at Texas A&M College of Medicine. His self-published medical memoir, When to Act and When to Refrain: A Lifetime of Learning the Science and Art of Medicine, is for anyone interested in the past and future of medicine. A Preston Hollow neighbor for more than a decade, Dr. Stone shares his thoughts on how medicine should change, coronavirus and more.

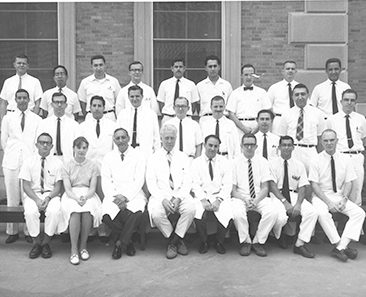

Barnes ward medicine housestaff, 1964-1965, Marvin J. Stone is sixth from the left on the first row.

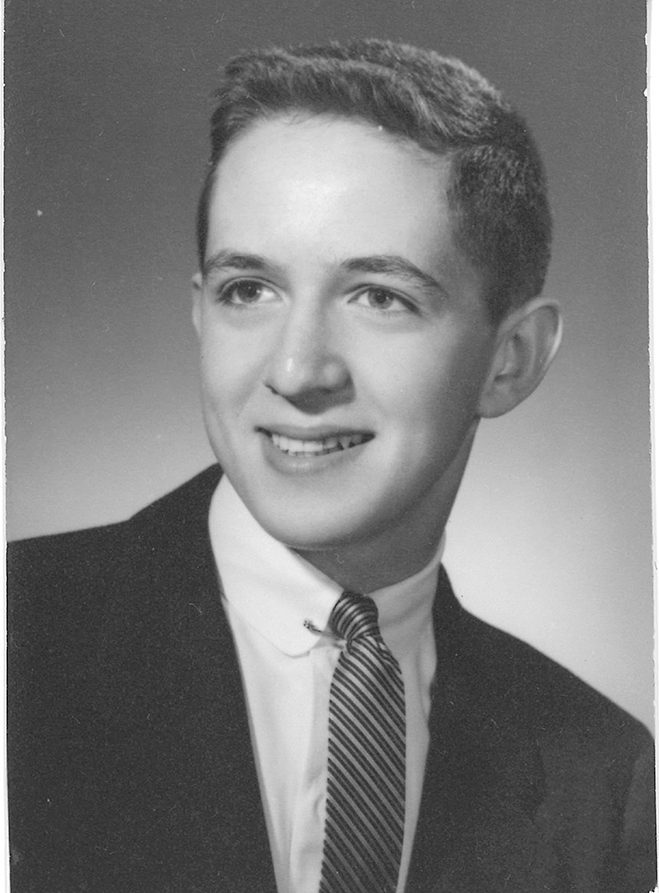

The Southwestern Medical School shack. Dr. Stone serves on the board of trustees for the Southwestern Medical Foundation.

Why did you choose your specialties?

It was easy to decide to go to medical school if I was accepted. Fortunately, I was. It was pretty easy to decide on internal medicine, but it took a while to settle on hematology and oncology.

What is the most difficult thing about those two areas?

They deal with patients who have serious, some- times fatal diseases. But it’s also rewarding, be- cause during my career we’ve been able to do a lot more for patients than we could when I started.

What do you hope readers gain from your book?

I wrote it because I consider myself so fortunate to have been able to serve as a physician. My hope is that one who reads the book would have some of my love for medicine and lifelong learning rub off.

How has the medical field changed over the course of your career?

Oh, boy. Scientifically, it has changed a lot. The advances in immunology, medical genetics and molecular biology, as well as clinical medicine, have just been astonishing. How people react when they get sick hasn’t changed that much. People still are concerned and concerned about their family, their future. It’s the same as it was 100 years ago.

How do you think the coronavirus has been handled?

It remains very difficult. We faced a pandemic without good diagnosis and treatment

What do you think needs to happen for prescription medications to be more accessible?

It’s a complex question. With companies that sell drugs, the push for prof- its is sometimes overwhelming. People have to pay exorbitantly high prices. If you look at the prices of similar medicines in other countries, sometimes they’re a lot lower. It would seem that there ought to be some way to lower prices so that people can afford them.

Why is “refraining to act” so important?

Sometimes you’re not sure how to act because you don’t have the in- formation or the data to make a clear-cut diagnosis. Or if you do have a clear-cut diagnosis, you may not have effective therapy. If the course of a patient’s disease has a slow tempo and doesn’t require therapy, it’s best to step back and see how things develop. William Osler and other physicians had an old thing called “tincture of time” — that time was the best therapy for some patients.

How would you say the Dallas medical community has changed?

Medicine is a lot more crowded, in the sense of more physicians being available. For instance, I can tell you that when I started in Dallas, in hematology and oncology, there were three specialists in the whole city. Now there are probably 30 or 40 at least. We certainly need more primary care physicians, really more than we need specialists.

How would you change medical education?

I’d get rid of the debt. There might also be ways to streamline medical education so it doesn’t take quite as long and still be as effective for young doctors.

What challenges are your students facing?

The applicants for medical school seem to be at or near an all-time high. On the other hand, medical student debt is a big problem. I had a scholarship offer pretty much all the way through medical school. It really was a tremendous help.

Why did you start teaching?

I got a taste of it when I was a student and a teaching assistant. I realized students teach you as much as you teach them.

What’s your favorite part of teaching?

Oh, my goodness. I like pretty much all of it. Hearing a student, an intern or resident present a case and try to figure out the diagnosis is a big challenge. It’s extremely worthwhile, sometimes very difficult and sometimes impossible.

DID YOU KNOW?

Dr. Stone has collected antique microscopes for the better part of 20 years. “Being a hematologist oncologist, I use a microscope pretty much every day to look at blood smears or bone marrows.”

What would you consider the most impactful moment in your career?

The interchange between teaching, re- search and clinical work, and seeing how each one of them reinforces the other.

What do you miss about clinical work?

I still miss the patients.

Is there a patient who left a lasting impression on you?

In the book, I talk about several of them and about the challenges that we faced in trying to unravel complicated clinical conditions. They are marvelous patients to have, and I always appreciated the opportunity to try and take care of them as best I could.

Why did you stay at the Baylor Sammons Cancer Center for so long?

The Cancer Center in Baylor started at the same time I went over there. We had an opportunity to build a new department and a new unit. It was very rewarding in terms of seeing a new kind of clinical department, to attract other physicians and see that place grow. I had a wonderful time.

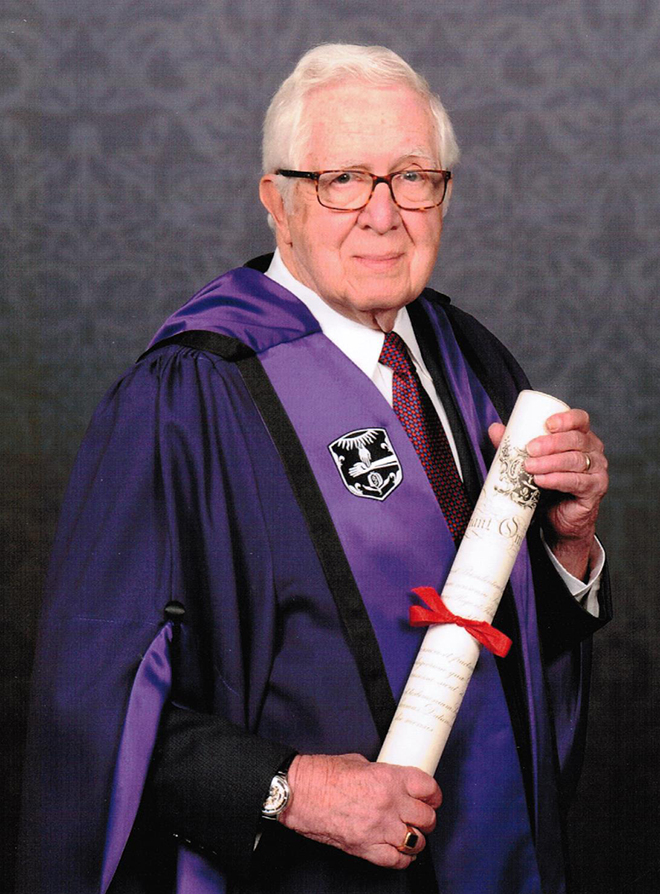

How did you become a member of the Royal College of Physicians?

I was inducted into that. I’m not sure why. But I am honored.

What’s it like serving on the board of trustees for the Southwestern Medical Foundation?

It has been very stimulating. Since becoming a member of the Foundation, I had the opportunity to develop some scholarships for students and to see how the Dallas community has been so gracious and so philanthropic.

This interview has been edited for brevity & clarity.