Stoney Burns and Kris Kristofferson

Brent Stein was born Dec. 4, 1942, in Dallas. His father, Roy, owned a commercial printing firm called Allied Printing Co. And his mother, Esther, stayed at home. Stein had a sister, who was three years younger.

The Steins, a middle-class family, lived in North Dallas. Brent graduated from Hillcrest High School in 1960, and then he attended the University of Oklahoma for two years, spent a summer at Arlington State University and then transferred to the University of Arizona in Tucson. He joined Sigma Alpha Mu, which began as a Jewish fraternity, and graduated in 1964 with a degree in marketing and advertising.

When he moved back to Dallas, Stein spent a year at a radio station selling ads. Then he started working for his father’s printing company, which was the largest of its kind in Dallas at the time.

Around the late 1960s, he learned about Notes from the Underground: The SMU Off-Campus Free Press. It was published by students at SMU, where Stein was an adviser to Sigma Alpha Mu.

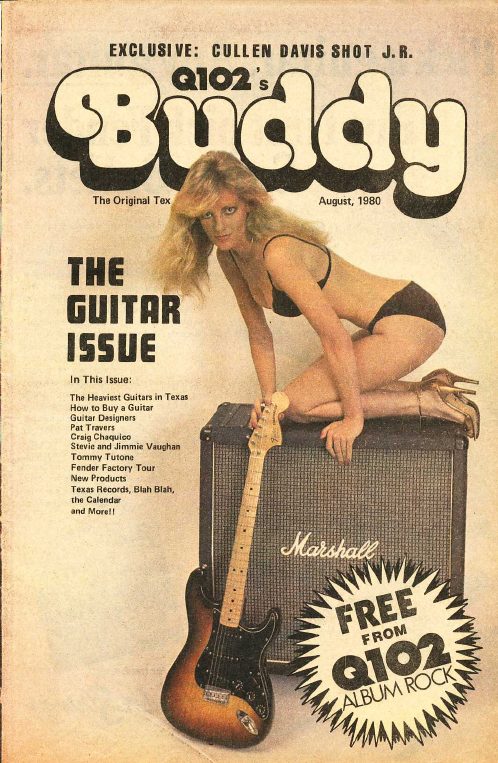

Buddy magazine 1980

Stein thought Notes could use a facelift, and he volunteered to help with the graphic design. He began using the name Stoney Burns to avoid embarrassing his family or clients, and eventually, that’s what almost everyone called him. He added white space and eye-catching cover art to the pages, and he created a new logo.

For one issue, Burns wrote the cover story, “Cops Start Anti-Love Campaign!,” took the photographs and arranged them in a collage surrounded by hippie art.

He also started a column in the paper, “Underground Undercurrents.”

As he worked with Notes, he let his hair grow to his shoulders, and his father fired him. So Burns became much more focused on the publication. By 1967, he had taken over as editor. The founder of Notes, Doug Baker, was the son of a man who worked for Clint Murchison Jr., founder of the the Dallas Cowboys. Murchison told Baker’s father that Baker needed to end his association with the publication.

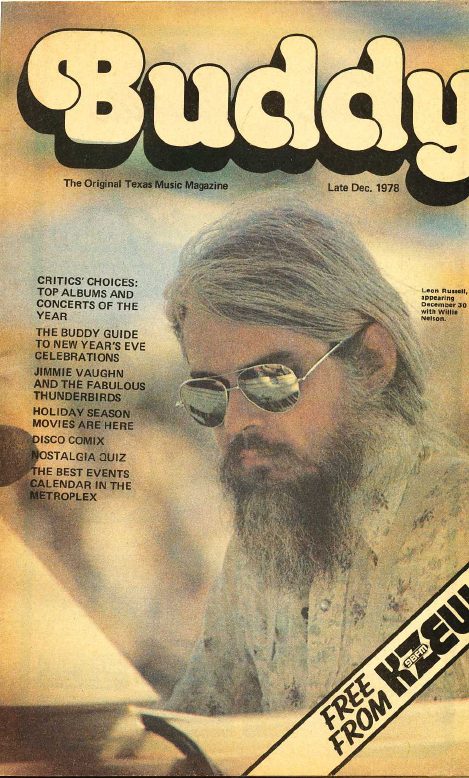

Buddy magazine 1978

After Burns took over, SMU President Willis M. Tate asked the publication to remove any mention of the university from its title and kicked it off campus.

Notes was anti-war, anti-racist, advocated for hallucinogenic drugs and provided information about birth control and abortions.

While leading the publication, Burns was arrested multiple times and beaten up, his tires were slashed, his car was shot, and the office was vandalized.

In mid-September 1970, Burns left Notes. He sold 999 shares to the Fort Worth White Panthers for a marijuana cigarette, which they smoked to seal the deal.

Then he worked for a month at the Lone Star Dispatch in Austin before returning to Dallas to work with Baker at alternative newspaper Dallas News, where he was the art director, sold ads and wrote a gossip column. The News was renamed Iconoclast.

Burns decided to run for Dallas County sheriff in 1972, and within a month of his announcement, he was arrested for possession of a small amount of marijuana. He was sentenced to 10 years and a day in prison, and while waiting for the outcome of his conviction’s appeal, he left the Iconoclast and started Buddy, a music magazine named for Buddy Holly.

He spent a month in the Huntsville prison in 1974 before the governor commuted his sentence.

Two years later, he hired Kirby Warnock, who had just moved to Dallas. There was no interview; Burns just wanted to know if he could sell advertising.

“It was the most fun I’ve ever had and the craziest time I’ve ever had,” Warnock says.

Though he was hired for a sales position, Warnock mostly wrote articles and took photos for the magazine during his eight years there. As an editor, Burns was a stickler for grammar.

Their office was on McKinney Avenue near Lemmon Avenue, in two adjoining units of an apartment building. It was cheap, Warnock says.

“He was a great guy to be around,” Warnock says. “We just had a lot of fun. That’s what I remember, is having fun.”

Source: “Stoney Burns and ‘Dallas Notes’: Covering the Dallas Counterculture, 1967-1970” by Bonnie Alice Lovell