Jennifer Troice’s vaulted, multi-level home stands out, even on a street of dazzling dwellings constructed after a 2019 tornado leveled much of Pemberton Drive.

Behind the stately exterior resides a warm, creative family of five, including Troice’s husband, Jamie Haidenberg, M.D., plus one bouncy, bilingual silky-soft bernedoodle named Maya. (“Abajo,” Maya is told when she jumps to greet visitors.)

Troice’s geometric-minimalist-style sculptures are displayed throughout the house.

There’s a show-stopping, three-foot bald eagle (a gift to her husband), black bear and gorilla from her endangered species collection; an array of silhouettes seated on shelves, willowy limbs dangling; and a series of free-standing human hands signaling messages of happiness and love.

Sons, ages 8, 7 and 4, have contributed colorful dinosaur statuettes. A polychromatic sea turtle represents a collaboration with local painter Jenny Grumbles.

Troice came to Dallas after the 2019 twister, but she has weathered personal storms. She has experience smashing and rebuilding, which can be therapeutic, she says.

Troice doesn’t specify the circumstances of a traumatic incident she suffered when she was 17, living in Mexico City, but she says the painful event powered her art career. Someday she will discuss her history in more detail, she says, but for now her kids don’t need to know everything.

“Before that experience, I loved art, I studied music, played piano, harp, but I did not have the creative spark in me,” she says. “But afterward, my first little collection just poured out. I didn’t stop, like art therapy without knowing art therapy existed.”

There was no defined style then. She made “a little bit of everything.” And once that first series was done, she broke and burned the whole lot.

“It was like closing my circle and saying OK, now I’m going to start making nicer things.”

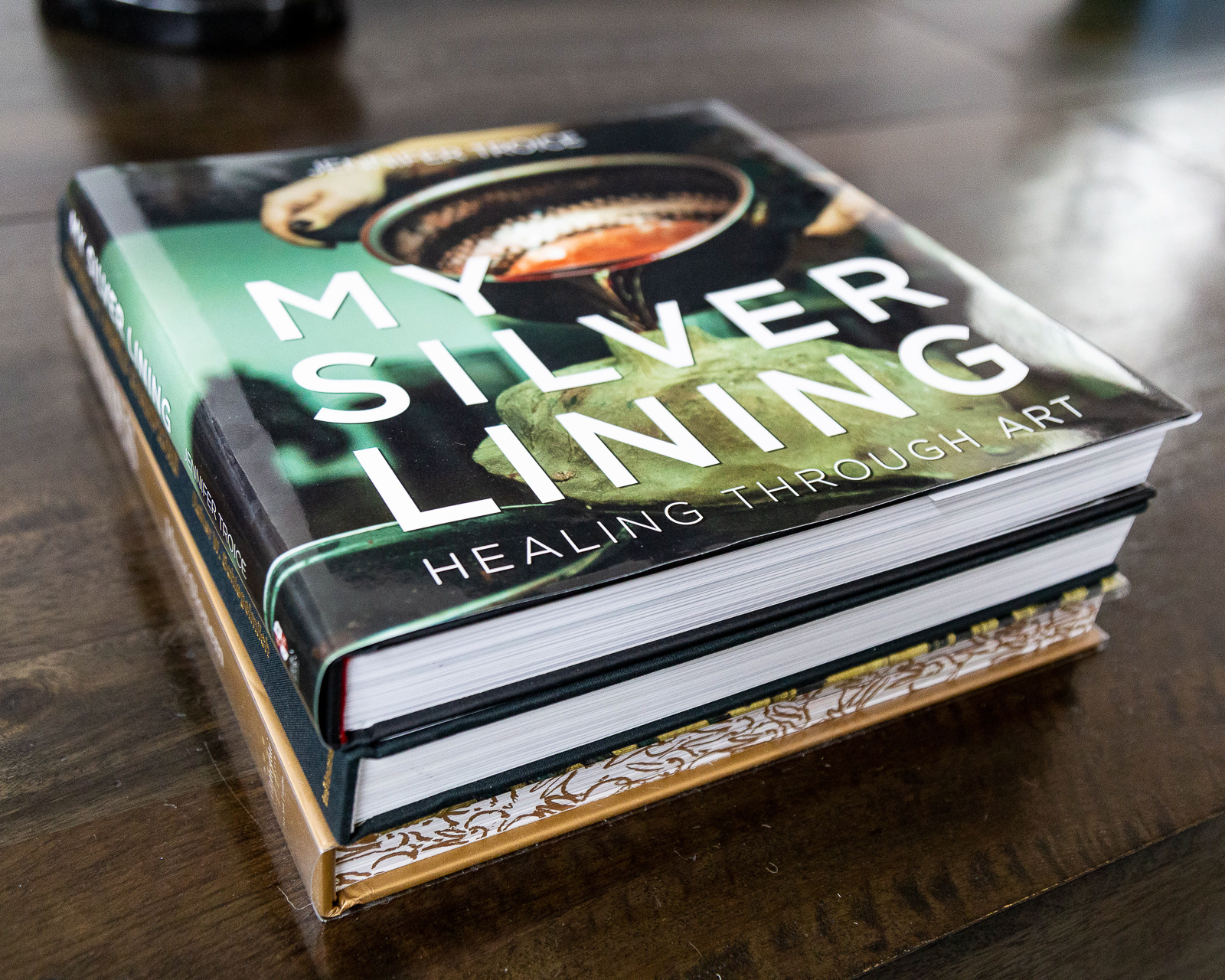

This year, she published a coffee-table book, My Silver Lining: Healing Through Art.

Pages contain breathtaking photos and stories about her life, work and noteworthy collaborations. Several are dedicated to a picture-by-picture description of the laborious casting procedure.

“Sculpting is an intense process, and Jennifer has mastered it,” says Esther Lewin, a teacher at Dallas’ Early Childhood Education Center who reviewed the book.

“Her skill and passion are unlike others. Each piece has a meaning and a story.”

By 21, Troice completed her first large-scale installation. In the lobby of the cancer center in Mexico’s American British Cowdray Hospital, bronze human “Helping Hands” appear to reach out of the walls to comfort visitors. Later, in a new wing of the hospital, she sculpted a one-ton “Tree of Life.”

Rhea Braniff, the woman who commissioned those pieces on behalf of the hospital, died of pancreatic cancer just as Troice was finishing “The Tree of Life.” A bird nestled within the squared-off metallic leaves is dedicated to Rhea, with whom she had become close friends, Troice reveals in her book.

Before leaving Mexico, the mother and artist left a whimsical family-themed mark on a Veracruz park, building life-sized bronze figures and interactive pieces including a see-saw with a built-in playmate affixed to one seat.

It took about three months, and her sons — the youngest but a few months old — were there for it.

“It was really fun to work on this with my kids,” Troice says. “I like that they learn not only how to make a sculpture but that there’s a certain order to making things, and you have to have patience, wait for things to dry, you can’t just skip to the end.”

While Troice misses certain things about Mexico, she says Preston Hollow, where her boys attend St. Mark’s, is a better place to raise a family. And it is a good place to be an artist.

“you have to have patience, wait for things to dry, you can’t just skip to the end.”

“Dallas has a wonderfully tight-knit art community, where artists support and show up for one another.”

A potentially disabling neurological disease also failed to bring Troice down. Instead, a 2021 multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis opened more doors to healing and helping others.

Today she’s on the committee of the Yellow Rose Foundation Gala, a Dallas event that raises millions each spring for MS research. Gala promos boast that Troice has “generously donated her sculpture, ‘Cubist Horse,’ to be featured in the live auction.”

That item, an entrancing isometric equestrian bust in lost wax bronze casting, sits in a room off the entryway amid stacks of envelopes, boxes, giveaways and gift bags containing palm-sized, squishy “stress roses” — Troice is in the throws of organizing for the April fundraiser.

She believes science is on the cusp of eradicating MS, a faith that fuels her altruism.

Twenty years ago there were, maybe, two treatments, she says. Now there are 22, and progress is still happening relatively quickly.

Medical professionals can be slow to identify the illness. She says she has suffered symptoms — “like pain all over the body, but feet, mainly, like I am stepping on needles” — since she was 13.

The type of artwork she does is physical, requires hours of standing and heavy lifting, so at times she has traveled with a wheelchair.

She underwent a pointless bilateral leg surgery, thinking the problem was a tunnel syndrome, she says.

“I’m thinking, OK, that’s it. Nobody knows what it is. So I’ll just live with it. And in December 2021, I got my worst flare-up. I couldn’t walk. I lost muscle mass, was in extreme pain.”

That crisis ultimately led to a diagnosis, after which she was able to receive more targeted treatment. Conditions that plagued her for decades have improved.

“The next generation might not know what MS is or, hopefully it will be a remote disease, like polio. I have hope that it will happen in my lifetime.”